Adaptive Policy Prior in the Era of Experience

Rethinking the Goal of Offline Reinforcement Learning

Offline RL is traditionally framed as learning a policy from a static dataset

for direct deployment, where conservatism is essential to avoid extrapolation errors.

In the era of experience

This shift alters what offline RL should optimize for. The central claim of this post is that, rather than collapsing behavior to dataset support, a good policy prior should preserve behavioral flexibility by explicitly accounting for epistemic uncertainty. Outside the dataset, actions are not inherently bad—they are simply uncertain—and prematurely assigning them near-zero probability significantly limits downstream adaptation from discovering and amplifying useful behaviors.

We develop this perspective conceptually and show how it leads to a practical, Bayesian-inspired algorithm for offline RL in our accompanying paper.

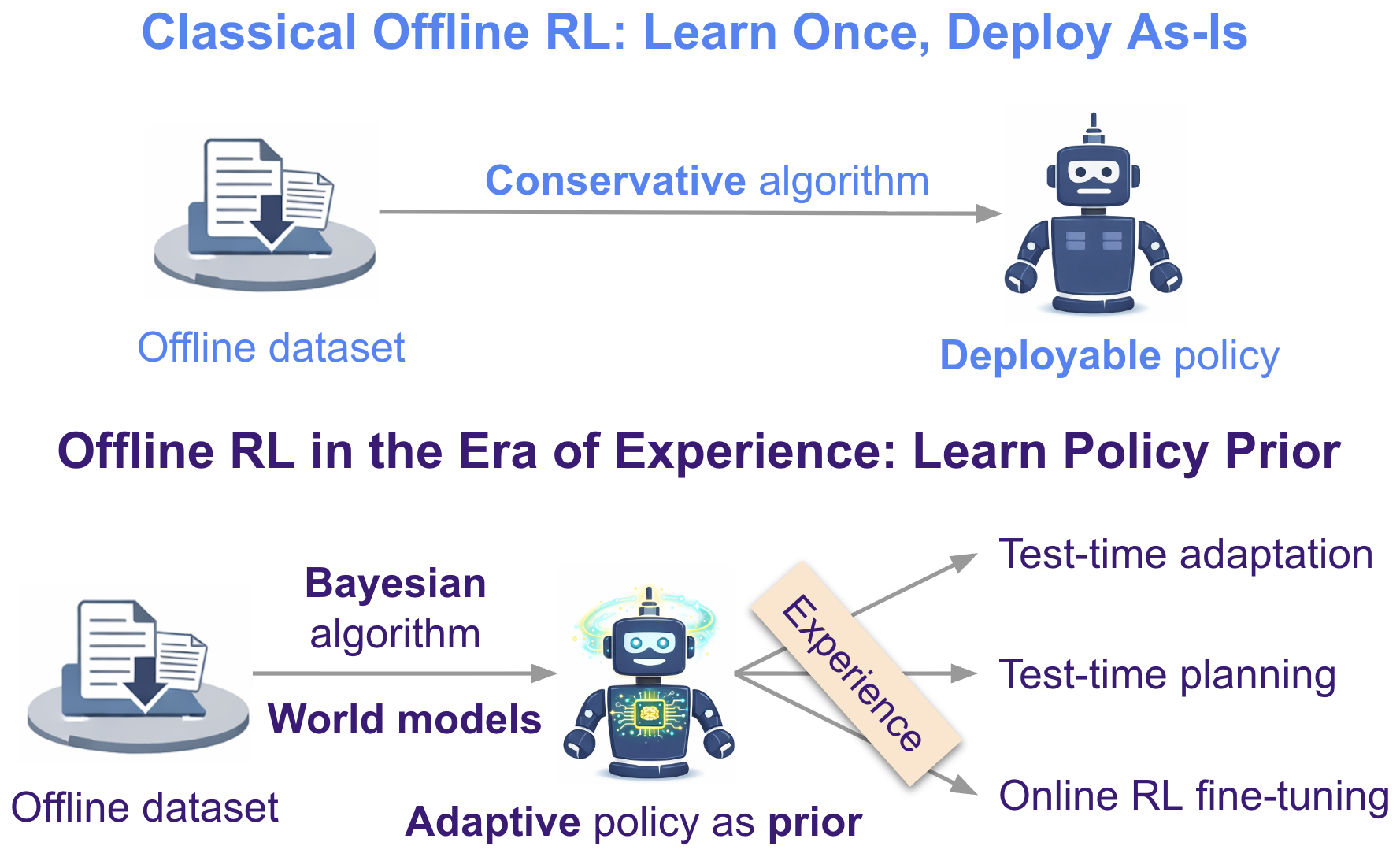

1. Original contract of offline RL: learn once, deploy as-is

Consider a static dataset $\mathcal D = \{(s,a,r,s')\}$ collected by some behavior policy $\pi_{\mathcal D}$.

In its classical formulation, offline RL learns a policy $\pi$ from a static dataset $\mathcal D$ for

direct deployment, without further interaction or adaptation

Imitation learning as the simplest expression of this goal

Behavior cloning makes this logic explicit. It treats the dataset as demonstrations and imitates

the behavior policy $\pi_{\mathcal D}$ via maximum likelihood:

$\max_\pi \sum_{(s,a)\in \mathcal D} \log \pi(a \mid s)$.

To go beyond pure imitation while retaining the same deployment contract, offline RL methods

attempt to extract useful signal from suboptimal data. A common example is weighted behavior

cloning

Despite its simplicity, imitation learning highlights the limitations of the deployable-policy contract. It requires coverage of near-optimal behavior in the dataset and implicitly assumes that test-time conditions closely match those seen during training.

Conservatism principle: resolving uncertainty via pessimism

Including behavior cloning, most offline RL methods are built around conservatism: actions outside the data distribution are treated as bad by default. Informally, we denote the behavioral support $\mathrm{supp}(\pi)$ the set of actions that are sufficiently represented under policy $\pi$. Under this convention,

$$ a \not\in \text{supp}(\pi_{\mathcal D}) \implies a \text{ is treated as bad} $$

Let $\pi_{\text{deploy}}$ denote the policy learned by offline RL and deployed in the environment.

Conservatism then induces a support contraction:

$$ a \not\in \text{supp}(\pi_{\mathcal D}) \implies a\not\in \text{supp}(\pi_{\text{deploy}}) $$

i.e., the deployed policy’s support is restricted to that of the dataset.

From a theoretical view, conservatism is connected with robustness

$$ \max_\pi \min_{\mathcal M\in \mathfrak M_\mathcal D} \mathbb E_{\pi, \mathcal M}\,\Big[\sum\nolimits_t r_t\Big]. $$

Under the deployable-policy contract—where

no exploration,

planning

2. What makes a good policy prior in the era of experience?

Preparing policies to adapt from experience

The classical formulation of offline RL treats the learned policy as the final product, optimized for direct deployment and therefore requiring strong safety guarantees. This formulation imposes two fundamental limitations: the learned policy is capped by the dataset's knowledge, and it cannot improve once deployed.

To overcome these limitations, modern AI systems increasingly operate in what Silver and Sutton call the

era of experience, where learning continues through

“data generated by the agent interacting with its environment”

A typical training pipeline illustrates this shift:

- Pretraining learns a base policy $\pi_0$ from large-scale unlabeled data, using self-supervised learning (not offline RL).

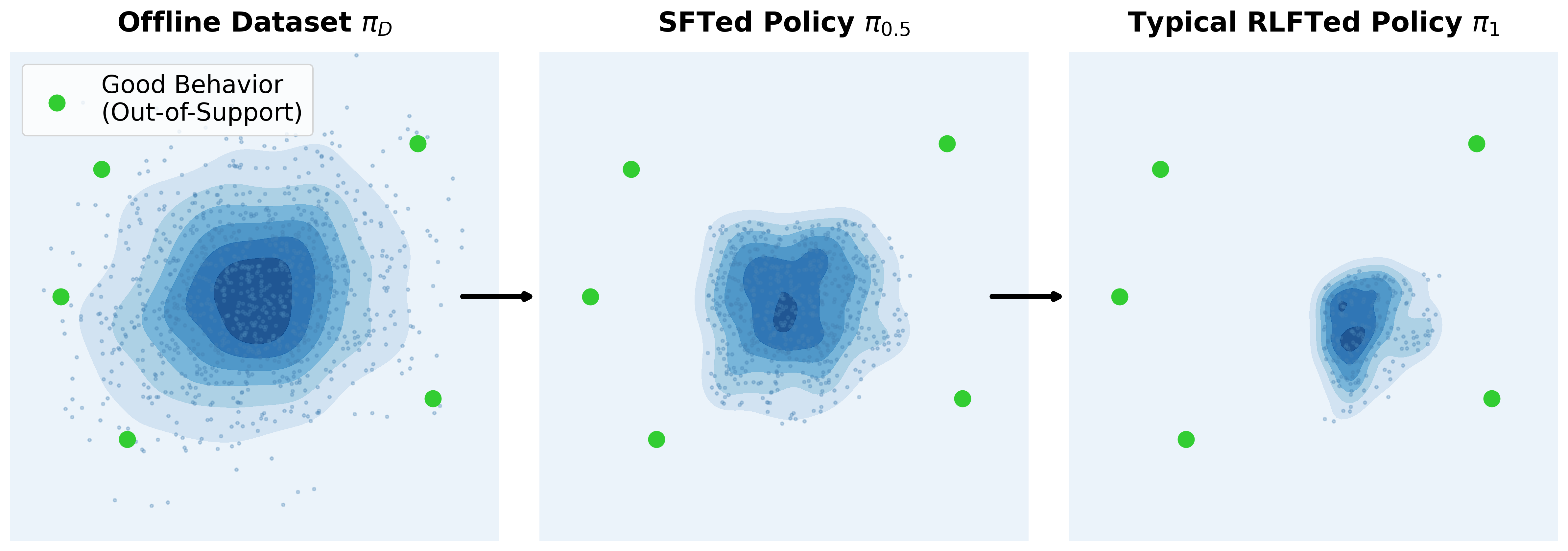

- Offline fine-tuning further optimizes $\pi_0$ into $\pi_{0.5}$ with a labeled static dataset, typically with behavior cloning (SFT). This stage closely resembles offline RL and we consider $\pi_{0.5}$ as the policy prior.

- Online reinforcement learning (RLFT) fine-tunes $\pi_{0.5}$ into a final policy $\pi_1$.

Here, experience encompasses both parameter updates (online RL fine-tuning) and test-time adaptation through in-context learning or planning based on the agent’s own interactions. Importantly, this does not diminish the value of offline learning: offline data provides a crucial prior that absorbs existing knowledge and reduces the sample complexity of subsequent experience. We now examine what properties such a policy prior should have.

Good prior for test-time scaling

Test-time scaling addresses the inevitable mismatch between offline data and the real environment by allowing behavior to improve through deliberation at inference time. Rather than sampling a single action from the current observation, an agent adapts using in-context memory or explicitly searches over multiple trajectories via planning.

These differences impose clear requirements on the policy prior. A good prior for test-time scaling must support history-dependent adaptation and maintain sufficient behavioral coverage to enable effective exploration during inference-time search, including actions that are underrepresented in the offline dataset. If potentially good actions are assigned near-zero probability, no amount of test-time compute can recover them.

Good prior for RL fine-tuning

Although RL fine-tuning improves behavior through online interaction,

empirical evidence

$$ a \not\in \text{supp}(\pi_{0.5}) \implies a\not\in \text{supp}(\pi_{1}) $$

When combined with SFT, this produces a compounding support contraction:

$$ a \not\in \text{supp}(\pi_{\mathcal D_{\text{SFT}}}) \implies a \not\in \text{supp}(\pi_{0.5}) \implies a\not\in \text{supp}(\pi_{1}) $$

The final policy is therefore tightly bounded by the SFT dataset’s behavioral support, even when better behaviors exist outside $\mathcal D_{\text{SFT}}$. From this perspective, a good policy prior should not be judged solely by its immediate performance, but by how much behavioral flexibility it preserves for downstream RL fine-tuning. An overly conservative prior may appear safe, yet actively restricting the space of behaviors that RLFT can amplify.

Good prior for generalization in reasoning models

As reasoning becomes a core capability of foundation models, it is no longer obvious that the learned policy should

strictly follow expert behavior, including expert-provided reasoning paths. Prior work

Summary. The common failure mode of conservatism is the same: avoiding uncertainty too early during offline training (e.g., the SFT stage), rather than allowing uncertainty to be resolved later through test-time scaling or RL fine-tuning.

3. How to go beyond dataset support?

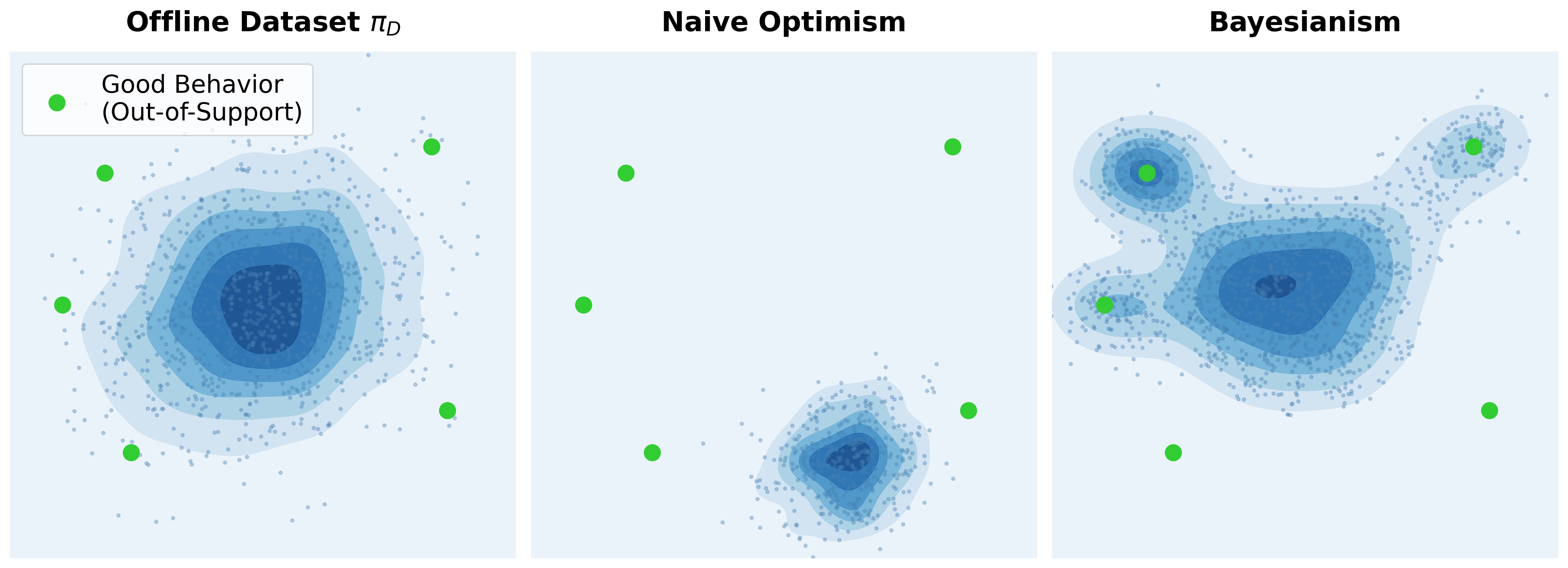

The previous section argues that a good policy prior must retain behavioral flexibility beyond the offline dataset’s support. The remaining question is how to achieve this without falling into unreliable optimism.

Why naive optimism fails in offline RL

A straightforward approach is to apply model-free off-policy RL directly to the offline dataset $\mathcal D$ by learning a

value function $Q(s,a)$ with Q-learning.

While this appears optimistic, allowing out-of-support actions to receive high value, it is fragile in practice. For an

unseen action $a_{\text{OOD}}$, the value $Q(s,a_{\text{OOD}})$ is never directly trained and is unconstrained by Bellman

consistency, leading to severe overestimation

Bayesian principle: resolving uncertainty via model-based adaptation

Out-of-support actions (and states) expose a fundamental ambiguity in offline RL. In the absence of data, we cannot determinately label an action as good or bad. Treating all unseen actions as bad collapses behavioral support, while treating them as good yields unreliable priors.

The Bayesian perspective resolves this tension by explicitly modeling epistemic uncertainty. Instead of

committing to pessimism or optimism, a Bayesian agent reasons over a posterior distribution of MDPs

$p(\mathcal M \mid \mathcal D)$, where each $\mathcal M$ is a plausible MDP consistent with the dataset $\mathcal D$.

The goal is to maximize expected return under this posterior:

$$ \max_\pi \; \mathbb E_{\pi, \mathcal M \sim p(\mathcal M \mid \mathcal D)} \,\Big[\sum\nolimits_t r_t\Big] $$

which is known as solving an epistemic POMDP

4. Bridging classical offline RL and adaptive policy priors

The discussion above motivates a shift in the goal of offline RL: from learning deployable policies to learning adaptive policy priors. Our paper, "Long-Horizon Model-Based Offline Reinforcement Learning Without Conservatism", sits at this transition point. Although formulated within the classical offline RL setting (i.e., learning from scratch without base models), the paper develops a practical, Bayesian-principled approach for constructing adaptive policy priors without relying on conservatism.

Illustrative example for test-time adaptation

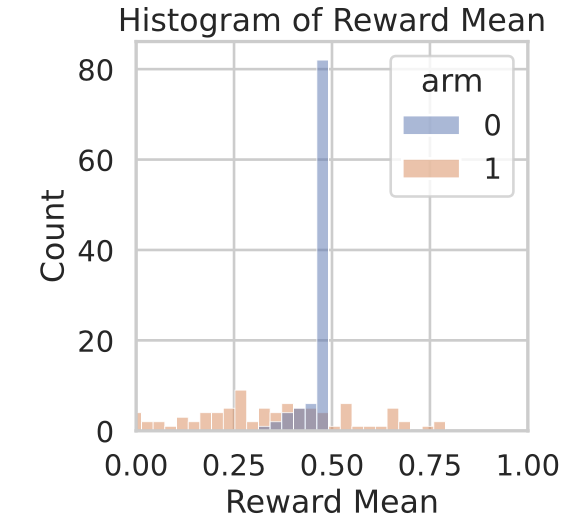

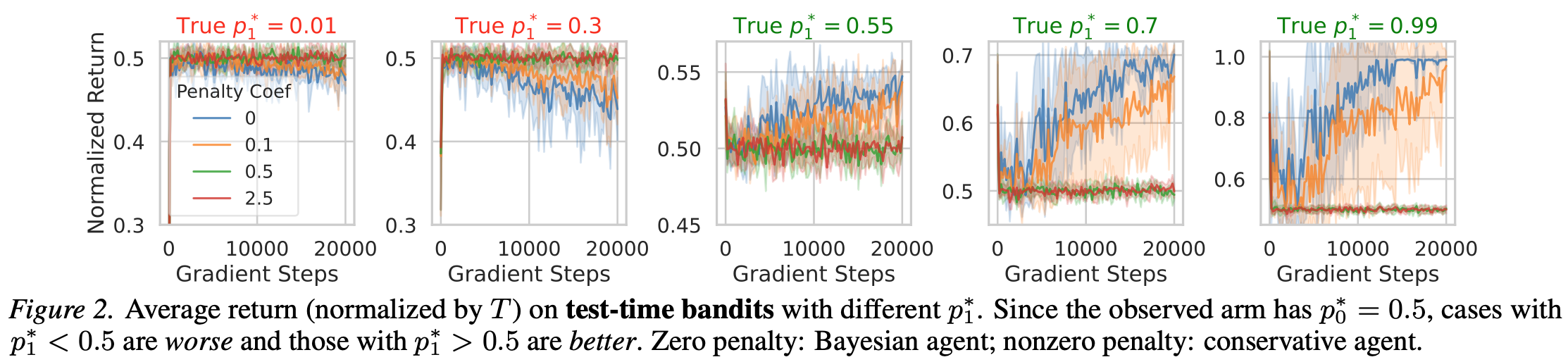

We illustrate test-time adaptation using the two-armed bandit example from our paper. The bandit environment has 100 interaction steps with an offline dataset $\mathcal D =\{(a_1, r_1,a_2,r_2,\dots,a_{100},r_{100})\}$ where two arms $a$ are labeled as $0$ and $1$, rewards $r \sim \text{Bernoulli}(p^*_{a})$, and $p^*_0,p^*_1$ are the true reward parameters. We construct a skewed dataset that contains trajectories collected exclusively from arm $0$ (i.e., $a_i=0, \forall i$); arm $1$ is completely unobserved. This creates maximal epistemic uncertainty over the reward of the unseen arm.

Following the Bayesian objective, we approximate the posterior over world models using an ensemble of $N$ reward models.

Epistemic uncertainty is quantified via ensemble disagreement: $U(a) = \text{std}(\{\hat R_n(a)\}_{n=1}^N).$

The ensemble predictions concentrate tightly on arm $0$ while exhibiting large variance on

arm $1$ as expected, i.e., $U(a=0) \ll U(a=1)$.

We train a history-dependent policy using this reward ensemble. To construct conservative baselines, we penalize predicted

rewards by uncertainty: $\tilde{R}(a) = \hat R_n(a) - \lambda U(a)$.

At test time, we vary $p^*_1$ to simulate two cases:

- Low-quality data case ($p^*_1 > p^*_0$): the out-of-dataset action (arm $1$) is better

- High-quality data case ($p^*_1 < p^*_0$): the out-of-dataset action (arm $1$) is worse

The two types of agents exhibit distinct behaviors:

- Bayesian agent: The agent initially explores arm $1$ to resolve uncertainty, then adapts its behavior based on observed rewards. It converges to arm $1$ in the low-quality case and returns to arm $0$ in the high-quality case.

- Conservative agent: With large penalty coefficient $\lambda$, the agent consistently selects arm $0$ in both cases. While safe in the high-quality case, this behavior prevents improvement in the low-quality case.

The low-quality data case is a stress regime, as offline datasets are typically curated to retain strong behaviors. Nevertheless, it highlights a key property of the Bayesian principle: it is more adaptive and tolerant to data quality. When data is high-quality, Bayesian agent commits to seen behavior after online adaptation.

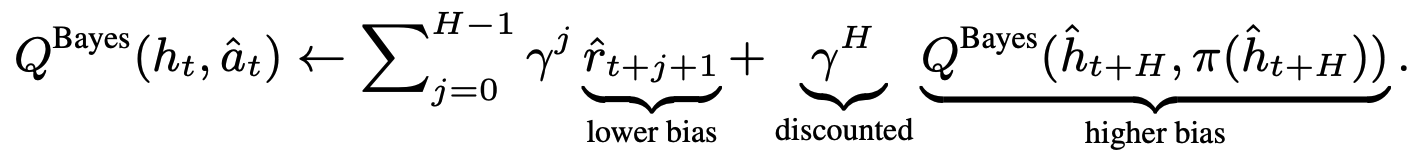

Why long-horizon rollouts matter once conservatism is removed

The Bayesian formulation naturally calls for long-horizon rollouts: ideally planning from an initial state

until the end of an episode. While this is trivial in the bandit example, it is challenging in general MDPs, where small model

errors can compound rapidly over time

However, short-horizon planning is closely tied to conservative objectives. Once conservatism is removed, short horizons

introduce a new failure mode: severe value overestimation

This effect is illustrated below: longer rollouts simultaneously achieve better real performance and lower estimated Q-value.

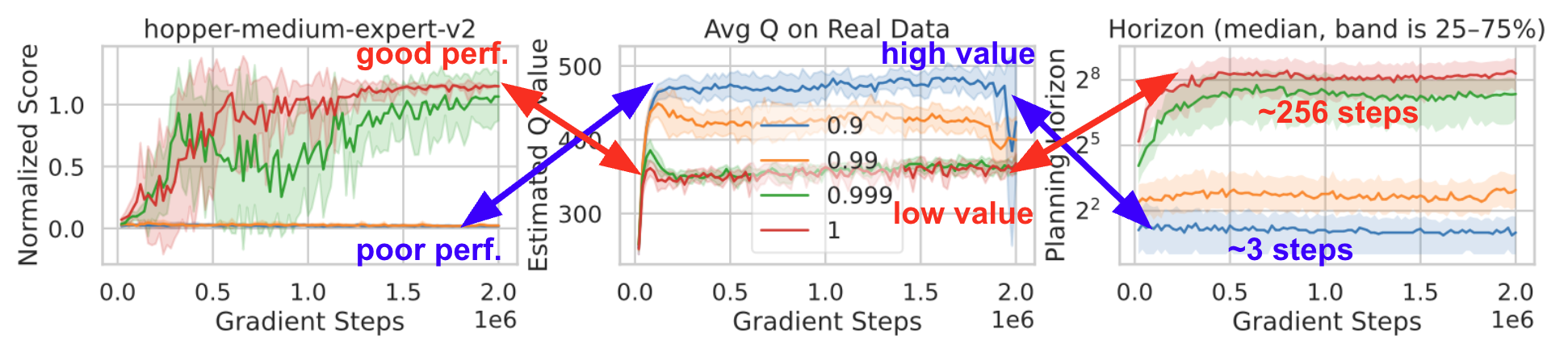

Long-horizon rollouts still face the challenge of compounding model error. To make them practical, we combine two ideas.

First, uncertainty-aware rollout truncation

Interestingly, even though model errors remain noticeable over long horizons, we still obtain good policy performance when using long-horizon rollouts. This suggests that policy optimization does not require highly accurate long-term predictions from any single world model. Instead, robustness to model error appears to be supported by ensembles that capture diverse plausible world models, allowing policies to generalize to the real environment. For readers interested in algorithmic details and full experimental results, we refer to the original paper.

5. Q&A

Q: Do you mean we should abandon conservatism in offline RL?

A: No. Conservatism is appropriate when a learned policy must be deployed directly without further adaptation. Humans are similarly risk-averse when acting in the real world. But when offline RL is used to produce a policy prior that will later explore and adapt, applying the same conservative constraints too early unnecessarily restricts learning.

Q: Isn’t exploring out-of-support actions unsafe?

A: Safety is inherently application-dependent. In safety-critical domains such as healthcare or finance, attempting unseen actions can indeed be unacceptable, and the classical direct-deployment contract is appropriate. In many other domains, including robotics and digital environments, exploration can be safely integrated through uncertainty-aware Bayesian principles, e.g., by uncertainty penalties.

Q: Is an adaptive prior only useful for online fine-tuning?

A: No. Adaptive priors are equally important for test-time adaptation, where behavior improves through in-context learning or search without updating model parameters.

Q: In foundation model post-training, does abandoning conservatism mean drifting away from the base model?

A: No. It is important to distinguish between dataset conservatism and model regularization. Abandoning conservatism here refers to relaxing constraints that keep the policy close to a narrow fine-tuning (SFT) dataset. At the same time, constraints relative to the base model are still maintained to preserve its broad knowledge and prevent catastrophic forgetting of general capabilities.

Q: How does uncertainty-aware rollout truncation differ from conservatism?

A: Truncation is not conservative because we stop rollouts but still bootstrap from a terminal value, rather than pessimistically terminating trajectories with zero reward.

Q: Isn’t relying on long-horizon rollouts unrealistic given model errors?

A: Long-horizon prediction is challenging, but it can be made practical by combining rollouts with uncertainty-aware truncation. As world models improve—through better architectures, generative models, and pretrained foundation models—the reliable horizon continues to expand.

Q: How well do existing benchmarks such as D4RL evaluate adaptivity?

A: D4RL includes low-quality and limited-coverage datasets, but its complex robotic tasks make it hard to diagnose how and where adaptation occurs. Simpler environments, such as 2D gridworlds, provide more controlled settings for missing behaviors and test-time condition shifts. Benchmarks that directly probe adaptivity are an important direction for future work.