RL Fine-Tuning Is a Stability–Plasticity Problem

Predicting When Policy-Centric or Dataset-Centric Methods Work

This blog summarizes and extends our paper "The Three Regimes of Offline-to-Online Reinforcement Learning", authored by Lu Li, Tianwei Ni, Yihao Sun, and Pierre-Luc Bacon.

In modern RL, training from scratch is becoming rare. A more common workflow is to first pretrain a policy on a static dataset, and then fine-tune it through online interaction. This paradigm appears across a wide range of settings: offline-to-online RL in control and robotics, SFT-then-RL pipelines in large language models and vision-language-action policies. The motivation behind this recipe is straightforward. Offline pretraining reduces the need for costly exploration, while online fine-tuning enables improvement beyond the limitations of static data. In principle, this combination should offer the best of both worlds.

In practice, however, fine-tuning pretrained RL agents is often fragile and difficult to reason about. Small design choices—such as whether to reuse offline data, how strongly to regularize RL, or how much to rely on the pretrained parameters—can have an outsized impact on performance. More concerningly, the same choice can lead to success in one task and failure in another, even when the overall setup appears similar.

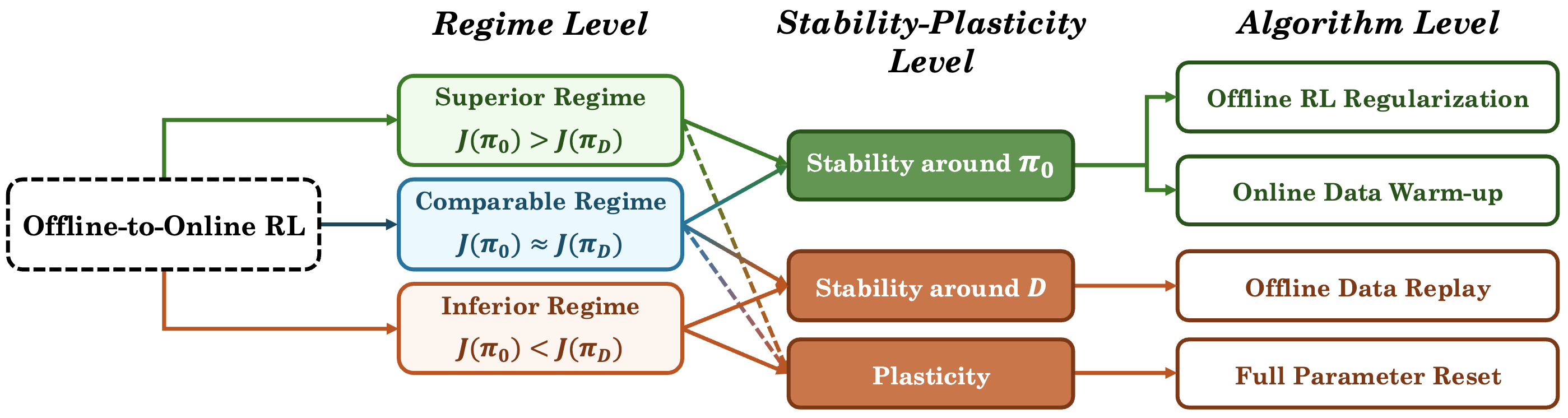

In this work, we propose a predictive, regime-based framework for RL fine-tuning. We show that many fine-tuning failures arise from preserving the wrong source of offline knowledge, and that identifying the stronger prior— the pretrained policy or the dataset—predicts which class of interventions is likely to succeed. Our framework is validated through an extensive empirical study in classical offline-to-online RL, spanning diverse tasks, pretraining methods, and fine-tuning strategies. Beyond this setting, the same stability--plasticity tension has direct implications for modern post-training pipelines.

1. The RL fine-tuning paradox

Consider a standard offline-to-online RL scenario. You pretrain a policy $\pi_0$ using your favorite offline RL algorithm—be it CQL, TD3+BC, or simple behavior cloning. You're ready to fine-tune online. Now you face a seemingly simple question: What should fine-tuning be anchored to?

Two dominant perspectives in the literature offer different answers.

Path A: trust the pretrained policy $\pi_0$. This strategy treats your pretrained policy as the golden starting point. Since you've already squeezed knowledge from the offline data, you focus on preserving the knowledge encoded in $\pi_0$. You might use an online data warm-up to collect fresh experience before updating, or apply regularization toward the pretrained policy.

Path B: trust the offline dataset $\mathcal D$. A different perspective emphasizes the offline dataset as the more reliable anchor. Instead of trusting the pretrained weights, you use offline data replay—continuously mixing your offline data with new online interactions. This prevents the policy from collapsing due to the sudden distribution shift of online interaction. In some cases, you even reset the model's weights to random initialization before fine-tuning, on the belief that offline pretraining may reduce the network's ability to continually learn.

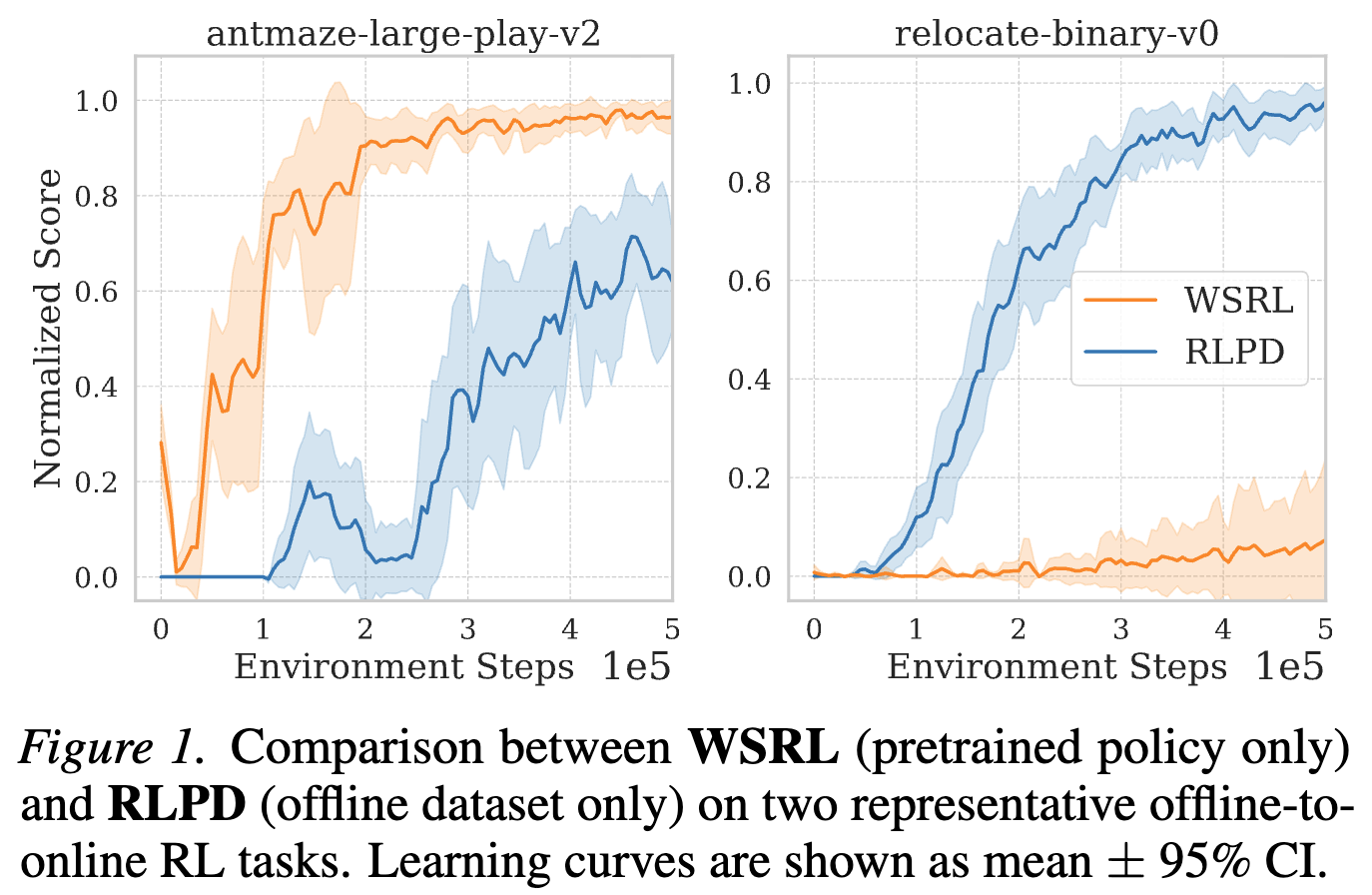

The unsettling observation

Both approaches are well-motivated and widely regarded as best practices in different strands of prior work. Yet when we compared them systematically, we observed a striking inconsistency.

On tasks such as antmaze-large-play-v2, $\pi_0$-centric methods

(e.g., WSRL

These outcomes are not easily explained by hyperparameter choices or implementation details. Instead, they suggest that a more fundamental principle is missing. What underlying factor determines whether a fine-tuning strategy succeeds or fails?

2. RL fine-tuning is a stability–plasticity trade-off

Choosing the stability anchor

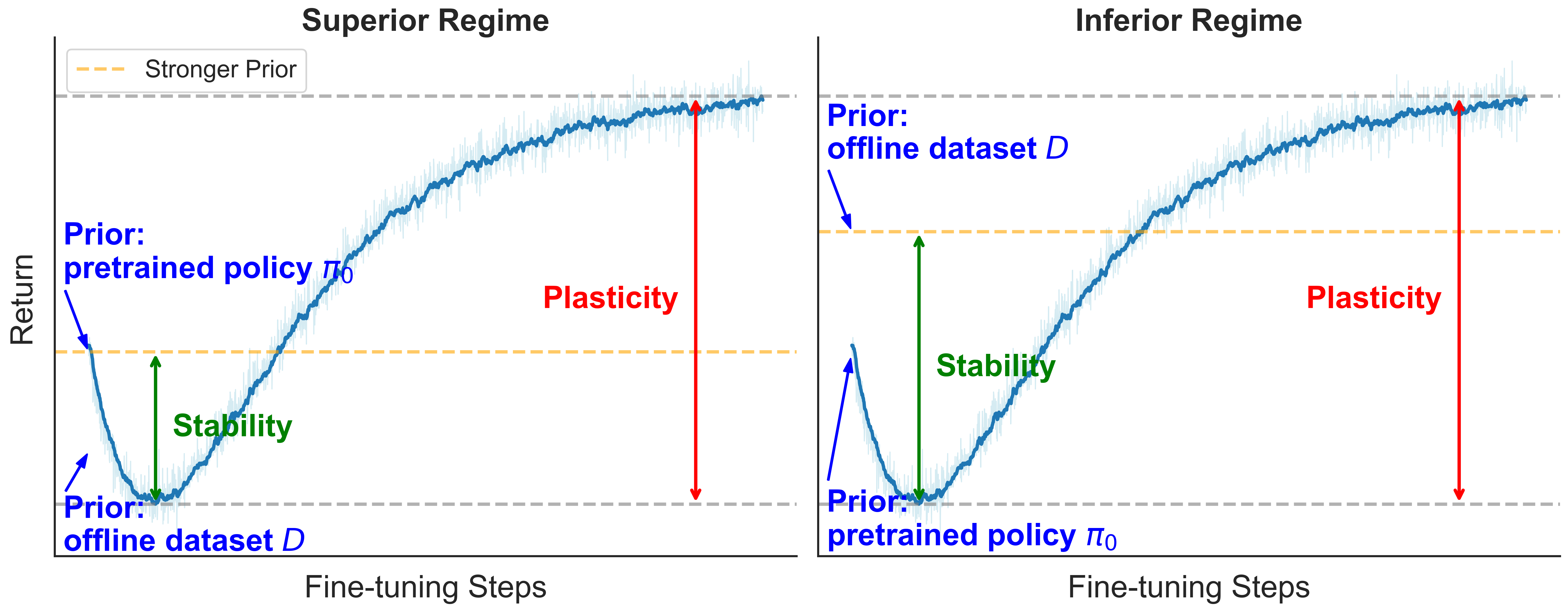

The tension behind the fine-tuning paradox is familiar from continual learning: you want to acquire new knowledge from online interaction without erasing what you already know. This is the stability–plasticity trade-off: stability preserves prior capability, while plasticity enables improvement from new data.

Offline-to-online RL adds a twist: at the start of fine-tuning you have two sources of prior knowledge. One is explicit in the pretrained policy $\pi_0$; the other is implicit in the offline dataset $\mathcal D$. Many methods privilege one or the other ($\pi_0$-centric vs $\mathcal D$-centric), but the paradox suggests neither choice is universally correct.

Our key observation is simple: a good stability anchor depends on which source is stronger in the current setting. When both are available, it is usually most efficient to preserve the best offline baseline, since sacrificing it introduces avoidable degradation that must later be re-learned online.

We therefore define the offline prior knowledge as

$$ J^*_{\text{off}} := \max \left( J(\pi_0),J(\pi_{\mathcal D}) \right). $$

Here $J(\pi_0)$ is the average return of the pretrained policy, and $J(\pi_{\mathcal D})$ is the average return contained in the dataset, estimated from its trajectories.

Knowledge decomposition: what determines the final outcome?

Consider the sequence of policies $\{\pi_n\}_{n=0}^N$ produced during online fine-tuning. The best performance achieved can be decomposed as

$$ \boxed{ \underbrace{\max_{0\le n\le N} J(\pi_n)}_{\text{Final knowledge}} = \underbrace{J^*_{\text{off}}}_{\text{Prior knowledge}} + \underbrace{\text{Stability}(J^*_{\text{off}})}_{\text{Degradation} \le 0} + \underbrace{\text{Plasticity}}_{\text{ Online gain} \ge 0}. }$$

This decomposition separates three contributions:

- Prior knowledge: performance available before online learning begins (the better of $\pi_0$ and $\mathcal D$).

- Stability term ($\le 0$): the worst degradation relative to this prior during fine-tuning.

- Plasticity term ($\ge 0$): the maximum improvement achievable from that worst point using online data.

Intuitively, stability limits how far performance is allowed to fall, while plasticity determines how much the agent can recover and improve. Fine-tuning methods differ primarily in how they trade off these two effects.

Three regimes of offline-to-online RL

With the decomposition above, the offline-to-online problem naturally falls into three regimes, determined by the relative strength of the two offline baselines:

- Superior regime ($J(\pi_0) > J(\pi_{\mathcal D})$): The pretrained policy contains more useful knowledge than the dataset. Fine-tuning should prioritize stability around $\pi_0$, favoring policy-centric methods.

- Inferior regime ($J(\pi_0) < J(\pi_{\mathcal D})$): The dataset contains better behavior than the pretrained policy. Fine-tuning should prioritize stability around $\mathcal D$, favoring dataset-centric methods.

- Comparable regime ($J(\pi_0) \approx J(\pi_{\mathcal D})$): Neither source clearly dominates. Both policy-centric and dataset-centric methods can be effective, with outcomes often sensitive to implementation details.

Across all regimes, plasticity must also be calibrated. When prior knowledge is weak, stronger plasticity is often beneficial; when it is strong, excessive plasticity can be harmful. Crucially, this regime structure is predictive rather than descriptive: it anticipates which class of fine-tuning strategies is more likely to succeed in a given setting.

3. Mapping the fine-tuning toolbox: what are you actually optimizing?

The regime-based framework above does not prescribe a single algorithm. Instead, it organizes fine-tuning methods according to what they primarily optimize: stability around a source of prior knowledge, or plasticity for adaptation. Viewed this way, most RL fine-tuning methods can be decomposed into a small set of intervention primitives, differing mainly in degree.

-

Stability relative to $\pi_0$:

-

Online data warmup with $\pi_0$ before fine-tuning

, reducing distribution shift -

Conservative RL losses on online data

, anchoring updates to data collected by policies evolving from $\pi_0$ -

Freezing the backbone network and training adapters

, providing strong stability around $\pi_0$ -

Fine-tuning only lightweight components (e.g., actor-critic heads in

VLA) or learning residual policies

, likewise enforcing strong stability around $\pi_0$ -

KL regularization between current policy and $\pi_0$

, enforcing strong stability around $\pi_0$ -

Small learning rate during fine-tuning

, providing implicit, weak stability

-

Online data warmup with $\pi_0$ before fine-tuning

-

Stability relative to $\mathcal D$:

-

Offline data replay with off-policy RL

, where the offline-online mixing ratio controls stability strength -

Offline data replay with conservative RL

, further strengthening dataset-centric stability

-

Offline data replay with off-policy RL

-

Plasticity:

- Resetting the subsets of the network or injecting noise into

pretrained weights

-

Full network reset

, discarding pretrained weights and yielding maximal plasticity - Learning-rate restarts

, injecting transient plasticity

- Resetting the subsets of the network or injecting noise into

pretrained weights

While methods within each category share the same objective, they differ substantially in how much stability or plasticity they impose. The appropriate degree is task-dependent and difficult to predict a priori.

4. Main empirical results

A standard but large-scale testbed

We evaluate the framework in the classical offline-to-online RL setting:

pretrain a policy $\pi_0$ on a static dataset $\mathcal D$,

then fine-tune online in the same environment using off-policy RL.

Rather than focusing on a single task or algorithm, we deliberately test

breadth.

Our study spans 21 datasets (MuJoCo, AntMaze, Kitchen, Adroit) adopted by WSRL

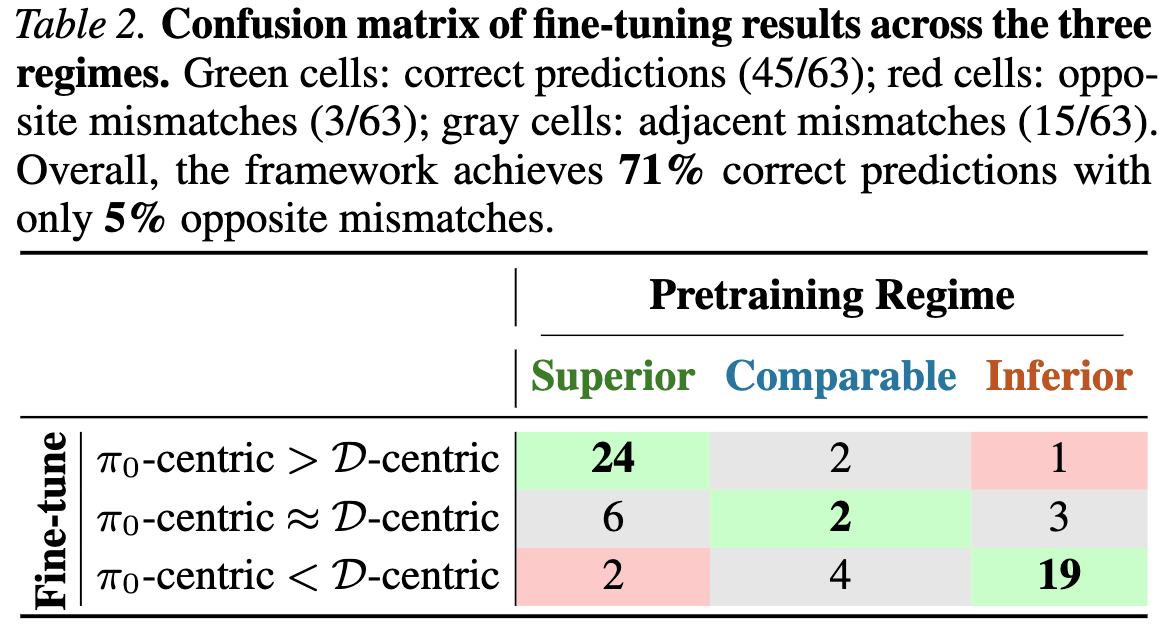

Prediction accuracy

We ask a simple question:

Do the best $\pi_0$-centric method outperform the best

$\mathcal D$-centric one in the Superior regime, and vice versa in the

Inferior regime?

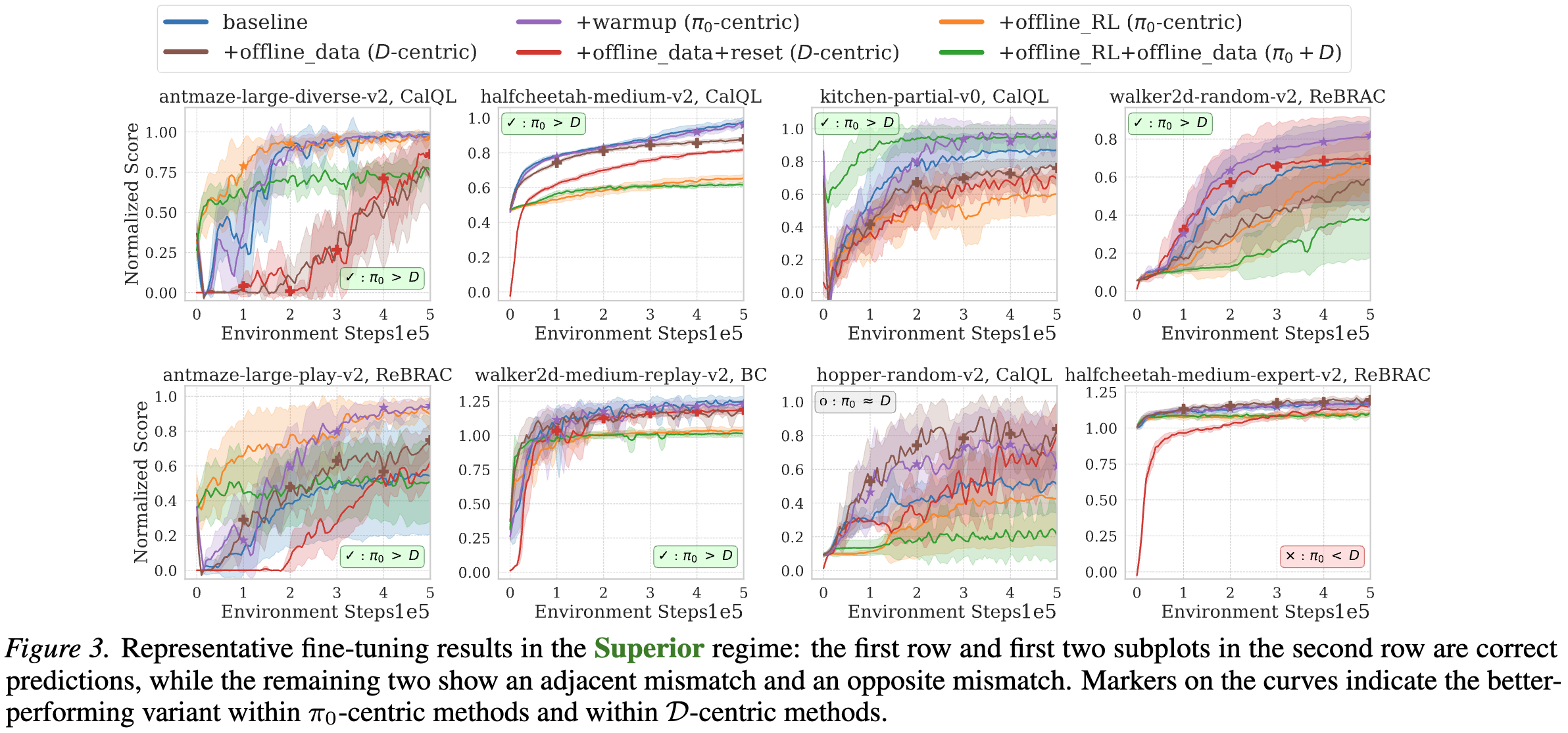

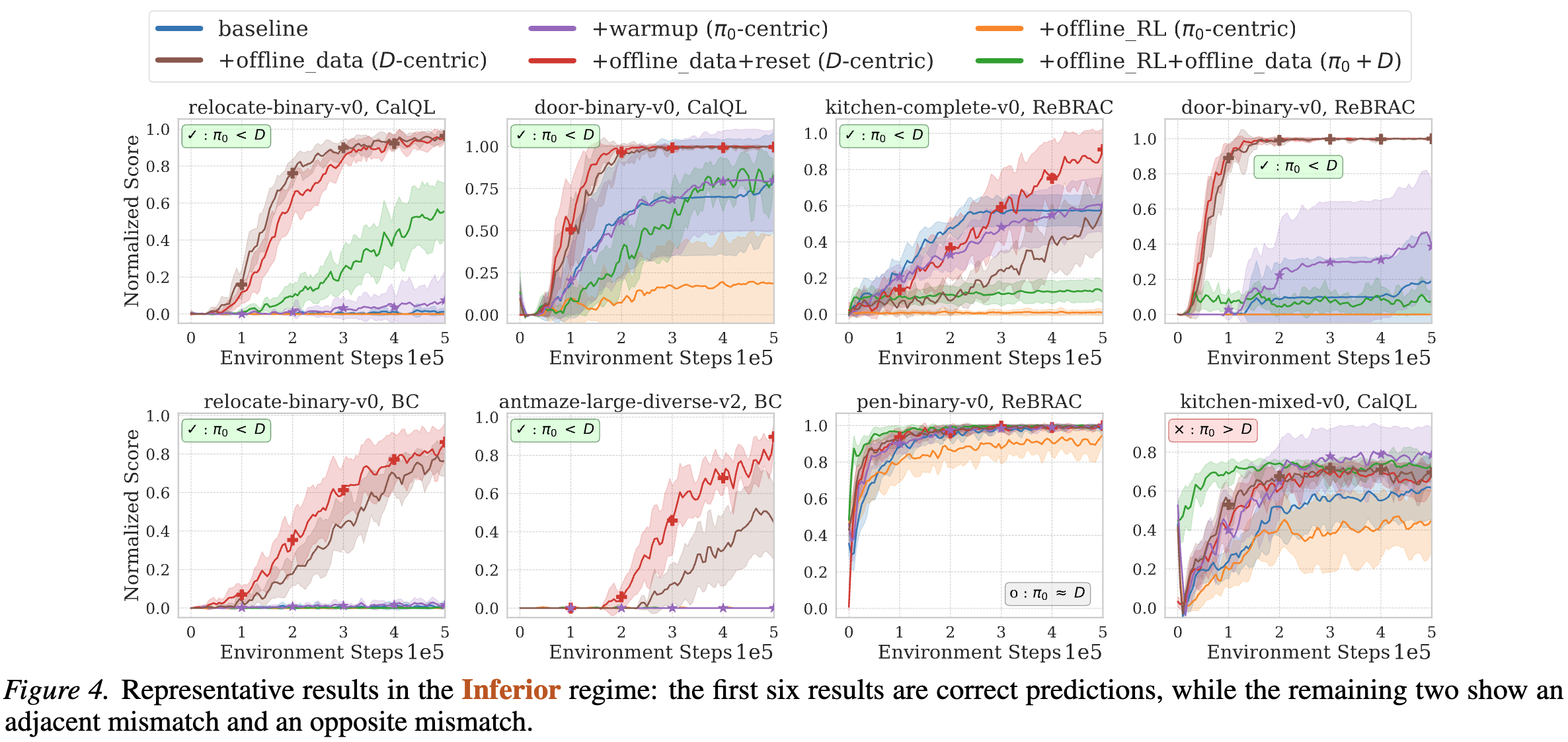

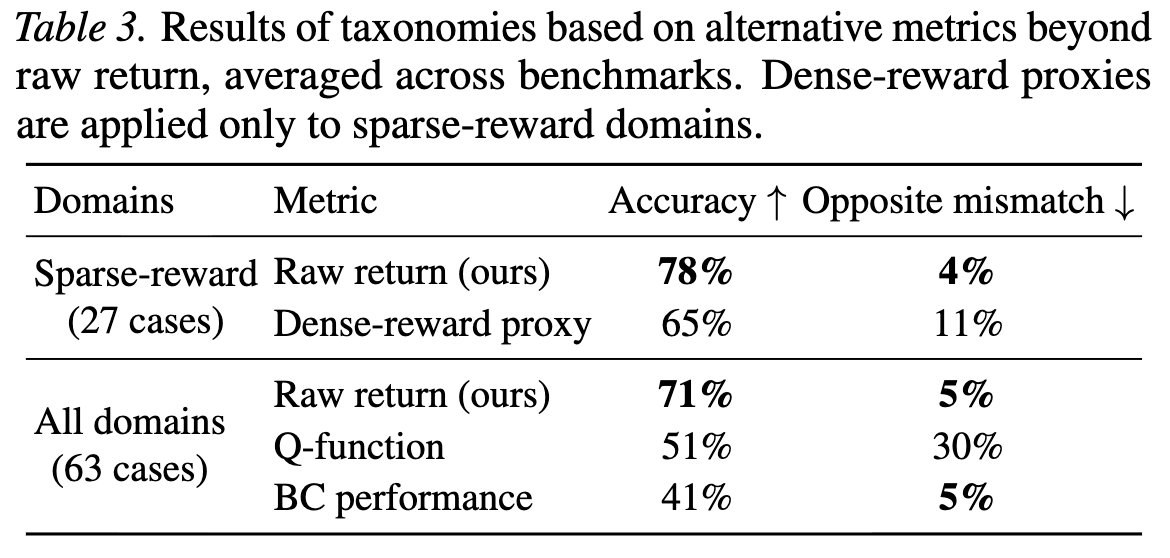

Across all 63 settings, the answer is largely yes. The framework makes the correct qualitative prediction in 45 out of 63 cases (71%). Only 3 cases (5%) show an opposite outcome and the remaining mismatches are adjacent. Imperfect accuracy is expected, given the influence of hyperparameters, implementation details, and the use of a simple raw-return metric for regime classification.

In the Superior regime, where the pretrained policy $\pi_0$ substantially outperforms the offline dataset $\mathcal D$, $\pi_0$-centric methods are typically more effective than $\mathcal D$-centric methods. Stronger stability proves beneficial primarily when $\pi_0$ is already close to optimal.

In the Inferior regime, where the pretrained policy $\pi_0$ performs substantially worse than the offline dataset $\mathcal D$, $\mathcal D$-centric methods typically provide more effective fine-tuning than $\pi_0$-centric methods.

5. Reading post-training practice through the regime lens

While our empirical study focuses on classical offline-to-online RL, the regime framework offers a useful lens for interpreting modern post-training pipelines, such as SFT-then-RL for LLM and VLA policies. Here, the SFT stage can be viewed as a form of offline RL via behavior cloning, followed by online fine-tuning with interaction or preference feedback.

Superior or Comparable regimes.

In many LLM post-training settings, powerful foundation models can closely match

the performance encoded in the SFT dataset,

placing the system in the Comparable (Superior) regime.

This helps explain why many approaches discard SFT data during RL fine-tuning

and instead emphasize $\pi_0$-centric stability,

using interventions such as KL regularization

Inferior regime.

Although a pretrained policy performing worse than its offline data may seem

undesirable from a classical offline RL perspective,

the Inferior regime is surprisingly common in post-training practice,

particularly in robotic settings with VLA policies

6. Common questions and clarifications

Q: Which fine-tuning method should I use in practice?

A:

The goal of our framework is not to prescribe a single algorithm,

but to identify which class of interventions is appropriate for a given setting.

Once the regime is identified, practitioners can focus on the corresponding toolbox

(policy-centric or dataset-centric) and tune specific methods and hyperparameters within it.

Determining the optimal degree of stability or plasticity remains an open problem

in RL fine-tuning.

Q: In the Inferior regime, why not discard the pretrained policy entirely?

A:

Full resets can indeed be effective in some cases and are included in our study.

However, even underperforming pretrained policies can provide useful structure,

particularly for exploration in sparse-reward long-horizon tasks.

In practical post-training scenarios, pretrained models also encode broad prior knowledge

beyond the offline dataset,

making complete discarding an often unnecessarily aggressive choice.

Q: Why use raw return to quantify the knowledge of a pretrained policy or dataset?

A:

Raw return is the direct optimization and evaluation objective in RL fine-tuning,

making it the most aligned and task-agnostic metric.

While it may not fully capture latent knowledge—especially in sparse-reward domains—we find

that alternative metrics such as dense reward proxies, Q-values, or behavior cloning performance

yield substantially weaker predictive power for regime classification.

Q: How are stability and plasticity related to the number of fine-tuning steps?

A:

Performance degradation typically occurs early in fine-tuning due to distribution shift.

Additional training steps can help recover and improve performance,

but only if sufficient plasticity is preserved. See the paper for a detailed analysis on the effect of fine-tuning steps.